Front Page News – Thunderball

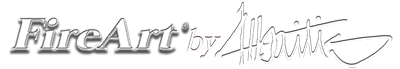

Las Vegas Firefighters Allan Albaitis, left, and Erik Thomason, right, battle a gasoline tanker truck fire Wednesday morning at Haycock Distributing Co. Inc. 715 W. Bonanza Road.

It looked like a Hollywood fire stunt. A cloud of fire laden smoke nearly blacked out the sun and darkened the several blocks from Station One to Haycock Distributing, a major distribution point for area filling stations. Not a place you want to see on fire. Bad juju.

Only twice in my fire/rescue career have I actually experienced an overwhelming sense of foreboding. The other was the MGM Grand fire in 1981. Looking at the towering pinnacle of fire I felt true dread. But, as so many of us know, that’s when you suck it up and like the ad says, “Just do it.” My attention turned to the two rookies with me and as we closed on the roaring blaze I put the bad feeling away somewhere and checked over our gear knowing we were going into some real shit. Rookies Eric Thomason and Jack Schlaff were my partners that day and in spite of the fact that I had almost eight years under my belt I still felt like it was a case of the blind leading the blind. There was just too goddamned much fire.

For years we had to endure the minute or two of getting off the rig, opening a compartment door and donning an air pack while people screamed at us. This was much mo bettah. In the short time we had to ride the few blocks we were geared up. Engine 10, an enclosed cab Pierce, allowed for us to step off the rig ready for a fight… but not ready for what I saw. We opened the captain’s side door and found ourselves less than 50 feet from this widowmaker firestorm. What in the hell were those guys thinking? It looked like the “DON’T” example in any book of tactics and strategies concerning tanker fires. When they blow they blow at the welded seams. These seams are around the circular front and back of the tank. We were perfectly lined up behind a raging gasoline tanker fire looking directly at the end of the rig. It was the worst place we could have been. The feeling of dread washed over me like a hot wind.

In seconds we were pulling off a couple of hundred feet of 2 1/2” line. Even though we were close I wanted a lot of line just in case our engineer got his mind back and moved the unit to a sane location. It never happened. We flaked out a shit-load of hose and positioned ourselves to the side of the time bomb thinking all the while, this is bad. This is bad. We’re in a tight spot.

The tanker was one thing but the exposure danger was supreme. Within spitting distance of the dock there were several 25,000 gallon above ground fuel storage tanks. Pipes, and valves were everywhere, and directly beneath us were several 25K underground tanks making the area a monster bomb ready to rock. We were in a real tight spot.

I-15 passes over Bonanza Rd. right at Haycock Distributing. I’m sure it was an interesting view from above. At least a dozen vehicles had pulled off to watch the fight. Onlookers were lined up like sparrows on a telephone line. Although the churning cloud of fire I’m sure was a sight to see, I got the feeling that they were waiting for more action. They didn’t have to wait long.

I’ve never considered myself to be faint of heart. I certainly have backed away from a few and once told a captain to kiss my ass when he tried to get me to cut a hole in a sagging, creaking roof. (As he was telling me my career was over for refusing an order, it collapsed.) I’ve even heard it said, “Ya got balls, Albaitis. Not much sense, but balls.” There’s no doubt in my mind that the Haycock fire marked the beginning of a change of heart for me. Maybe I got smarter that day.

I was starting to realize that we were far too close for the magnitude of that blaze. We had just opened the nozzle when I glanced back and saw a press photographer about fifty feet behind us clicking off shots like crazy. As it turned out, one of those shots was the front page of the Las Vegas Review Journal. Turning again to the fire I was about to open my mouth to tell Thomason and Schlaff that we should move our line back when it happened.

There was no warning. No time for a “This Is Your Life” flashback. Not even time for an, “Oh, shit!!!” There was only a tremendous shock and a sound so loud it was off the scale. Like a dog whistle that is so high pitched that it is almost beyond hearing, this was so loud that it nearly couldn’t be heard. But it sure as hell could be felt. A mind banging concussion slammed into us and we were hammered through the air skidding across the pavement for almost twenty feet. Not a Guinness record but a record in this fireman’s book. The next thing I was aware of was that we had survived a substantial gasoline tanker explosion. Afterwards, the driver said that the compartment that blew was a small one. Only 500 gallons. We had been jacked up by the equivalent of ten 50 gallon drums of gasoline popping off at the same time.

Chaos was running the show. In the distance I heard shouting. Jerry Douzat was the E-10 Captain that day. He was screaming at our rescue guys. “We got three men down. Get in there and get them, goddamnit.” At the time I didn’t understand that he was talking about us. Like I said it was a real loud noise. Glancing up at the Interstate I realized that the crowd of passersby was gone. Just gone. Out of the corner of my eye I caught the unattended nozzle starting to rise from the pressure and threatening to turn the hose into a lethal whip. At the same time Erik and I dove for it and shut it down to a manageable flow. It took a few seconds to take in what was happening. There was a mass exodus taking place. All I could see was the backsides of firefighters and civilians! What had been a scene of aggressive firefighting was now a confused tangle of people beatin’ feet as if Lucifer himself had just reared his head. We’re talkin’ a serious about-face! I’m not mentioning names but someone on the deck gun of Engine 10 was determined to pass firefighter Mo Higgins as she climbed down and stepped directly on her head while beatin’ a hasty retreat off the top of the rig. If I hadn’t just had the livin’ shit scared out of me it would have been funny.

In a matter of maybe thirty seconds Jack, Erik and myself were the only firefighters in my field of vision. Erik looked at me with eyes probably as wide as my own were and asked, “Should we run?” Oddly, it was the same question I was asking myself. I looked back at the south side of the property where another crew had been getting set up on a foam line. Foam is the only way to put out a gasoline fire. Son-of-a-bitch! They had regrouped and were getting ready to wade back in. My thoughts were all over the place but one thing stuck in my mind. By holding our position we were somewhat buying time for the rest of the guys. Although there was no effective extinguishment from our line it had to offer an amount of cooling and, hopefully hold off a potential large scale detonation. Could I live with being the cause of the death or injury of fellow firefighters if I bolted just because of a little explosion? Maybe I didn’t give it enough thought. Or maybe I gave it too much. I figured that there hadn’t been enough time to heat up a full tank of gas enough. But what if it wasn’t full. What if… My answer was, no. I couldn’t live with it. I reached for the line, looked at Jack and Erik and yelled, ”We don’t get paid to run. Hold your ground. Let’s put this bastard out.”

I have since mentioned this to those rookies (now veteran firefighters) and they both tell me they thought I was crazier than hell. They were probably right. If you look at the photo from the front page of the RJ you will be able to make out the front wheel of the truck just to the right of Erik’s air bottle. Using that as a scale I put the distance between us and the tanker at just over thirty feet. Thirty feet from a fully involved gasoline tanker that had just boiled 500 gallons of petrol and knocked our wicks in the dirt. Crazy? Oh yeah, I’d say so. And in this case, also very lucky.

Little note here: Since I’ve been asked by no less than 50 of the guys and gals on our department the answer is no! I did not soil my bunker pants and unless they are lying to me neither did Jack nor Erik. Actually, it was quite the contrary. As my old Gramps used to say, “He was so scared you couldn’t pull a banjo string out of his butt with a D9 Caterpillar Tractor.” I wasn’t that scared. I think a 9400 John Deere would have worked just fine.

It wasn’t until the foam hit it that the tanker fire actually started to go out. What a welcome sight! We also moved our line in closer and our Battalion Chief soon announced a knockdown. I think that is when I finally breathed again. That was also when I realized that I wasn’t nearly as secure in my decision to stand as I tried to appear. For a moment I truly thought I had gotten us killed. The foxhole prayers were flyin’. Maybe it wasn’t luck at all. Maybe it was my Guardians again. Whatever it was we were victorious and back in the days before a real Public Information Officer we didn’t mind braggin’ about it on camera. A local TV anchor cornered Erik and I and asked us what it felt like to be launched through the air.

An hour and a half later we were watching our answer on the 6 O’clock news back at Station 1. There was some pretty good video followed by a dramatic jolt at the moment of the explosion. Cut to: Two drenched with sweat firefighters with microphones stuck in their faces grinning like idiots. “Well, I tell ya,” the older one pronounced. “For a minute I didn’t know if I’d live to see tomorrow. But that’s the way it is with this job. Ya never know.” The guys were saying things like, “Right on, Albaitis,” and “Tell it like it is.” But I knew. I knew that for all my bravado and phony rhetoric we had dodged a major bullet. One spinning piece of steel could have punctured an above ground tank and turned the complex into Hell itself. In a classic training video probably watched by every fire academy since 1973 a railcar explosion killed the entire 13 man Kingman, Arizona fire department and injured 95 others. I couldn’t help but think about that.

While the guys whooped and watched another channel’s coverage I walked outside. A warm wind from the west furled the flags in front of the station. I looked at the lights of downtown Las Vegas. The clock/thermometer on the top of the Mint read 6:18 and 71 degrees. A few blocks away Vegas Vic waved his huge arm and said, “Howdy, Podner.”

A mundane thing, to be sure but it was one of those, glad to be alive moments. Thank God for Vic, I thought. But even more so, thank God for his fickle and unpredictable mistress, Lady Luck.

Categorised in: True Stories